Education in a Decadent Society

Ross Douthat didn't say much about schools in his book, "The Decadent Society." In this post, I explore how his analysis also applies to education, both before and during the pandemic. I end by noting where to watch for signs of a renaissance should one begin to take root.

Ross Douthat writes a column for the New York Times. He recently started a newsletter, "Reactions." He's calling it an exercise in "shameless book promotion" for the revised and updated paperback edition of his 2020 (pre-pandemic) book The Decadent Society. The change on the cover explains why a book in print for only a year needed revisions. The original subtitle, "How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success," is now, "America Before and After the Pandemic." More than book promotion, "Reactions" is a response to the question: "will the pandemic usher in a post-decadent renaissance?" I want to apply the question, as well as the broader themes in Douthat's work on decadence, to the topic of this newsletter, education in the United States.

Briefly for context, Douthat refers to decadence as, "economic stagnation, institutional decay, and cultural and intellectual exhaustion at a high level of material prosperity and technological development." Part 1 of The Decadent Society scans the societal landscape and finds stagnation, sterility, sclerosis, and repetition – his "four horsemen" of decadence – running wild. Part 2 looks at why decadence is likely to be with us for the long haul, and Part 3 imagines how decadence might come to an end. The book contains an odd mixture; it moves along with energetic analysis toward a melancholic conclusion. Sustainable decadence is here to stay.

Now, a year in to the pandemic, is that still the case? In "Reactions," Douthat writes, "Plagues can open new chapters in history, but it all depends on how people respond to them, what kind of responses are possible, and which pre-existing trends they accelerate or blunt." Across a week of posts exploring shifts and trends, he's sticking to his pre-pandemic, "sustainable decadence" conclusion: "I expect things to get worse before they get better."

While it may be unfair to condemn the possibility of a broader pandemic-birthed renaissance on a sector so brutally occupied by the four horsemen, the pandemic responses in K-12 do support Douthat's conclusion. Still, it's worth tracing decadence in education to consider how the advent of a renaissance could very well take root here. To that end, let's take a look at education before the pandemic, where we are today, and where to watch for signs of a renaissance taking root.

Pre-pandemic: Stagnation in Education.

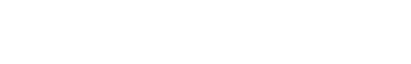

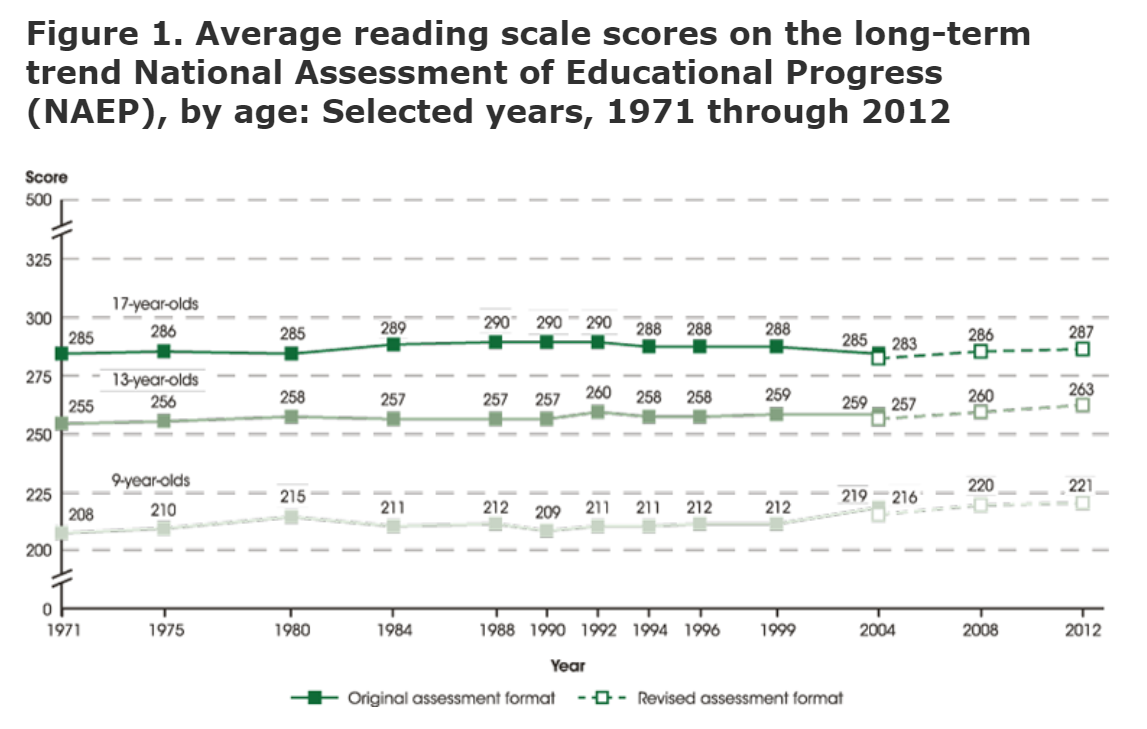

It's hard not to be cliché when describing how little has changed in education over the past several generations. Length of school calendar? Same. Teacher pay? Same. (since '89-'90 in '18-'19 dollars). Expenditures as a share of GDP? Same. Level of satisfaction with K-12 in U.S.? Same. Student learning outcomes in reading and math at ages 9, 13, and 17? Pretty much the same:

Same, too, for achievement gaps between White students and their Black and Hispanic peers across those age groups (pg. 67). What about the income premium of a college degree? Actually, this one is declining (though the share of adults over the age of 25 that completed 4+ years of college has risen from 5% - 35% since 1940).

In addition to college attainment growth, there are a few other areas showing evidence of change. Enrollment is up in charter schools. The population of home school students doubled through the early 2000s, growing from 800,000 to 1.77 million. It's worth noting, too, the growth in Hispanic student high school graduation.

There have been two primary strategies to produce more prosperity through K-12 educational improvements. The first was the move toward universal enrollment, including the subsequent variations on the enrollment theme, like: the addition of kindergartens, high schools, the expansion of formal, post high school options, and importantly, expanding educational opportunities to African Americans and other minority students, etc. The second was the effort to standardize the school experience, stretching back to older approaches like the Blue-Backed Speller to the creation of teacher training colleges, the use of annual student assessments, and more recently, the development a national set of common learning standards.

These strategies made education a core driver of economic growth across the early-to-mid 20th Century. "But," Douthat writes...

...this kind of change, from an unschooled population to an educated one, can really only happen once. Further improvements in educational attainment are certainly possible...but not on anything like that twentieth century scale. Any future improvement is likely to be a grinding process, constrained not only by policy failures and socioeconomic stratification but also by innate human capacities.

Like the good newspaper columnist he is, Douthat sums up pretty well the past 20 years of education reform in the United States. It's been a grind.

Education During the Pandemic

A year ago schools closed their doors and turned on their screens. As much as I appreciate individual educators, the pandemic has revealed just how uninspired and uninspiring our approach to education has become.

Writing in the Washington Post recently, high school senior Henry Smith describes his experience returning to in-person learning at his school in Falls Church, VA (Fairfax County Public Schools). It makes for a tough read.

I assumed that about 50 percent of students would opt in [to in-person learning]. The numbers didn’t go that way. On the first day back, my largest class had four students in-person; in the smallest, there were just two of us. On Friday, my largest class had 10 in-person students, but in another class, it was only me and the teacher.

My parents advised me to use the small class sizes to my advantage and to get the most out of being able to spend time with my teachers.

But the teachers aren’t dealing just with the handful of students in the classroom — they’re also teaching about 20 students online, and have to stay in front of the laptop camera. The students in the classroom ended up looking like extras in a low-budget movie. I felt like an afterthought, watching someone teach instead of being taught.

And that’s if the teacher was among those who chose to return and teach in person. If students are at the school but their teacher is not, they are sent to the auditorium, where they join their classes on school-issued laptops. Quiet is enforced by multiple teachers and administrators.

On the first day, I counted 19 students inside the auditorium during one period, mostly from classes other than mine — 19 students sitting for an hour, in masks, staring at screens and listening to a class using school-issued ear buds that don’t stay in your ears. In three of my nine classes — one-third of my course load — my teacher was not in the school.

The half in-person, half online approach Smith describes in Northern Virginia is similar to what I've seen in the larger school districts here in Connecticut. That approach may work from the perspective of balancing many competing needs – those of families (for childcare), of students (for safe places to be during the day), of local political leaders (for the talking point that schools are open for kids and families who need them), and of professional staff (for remaining employed despite not being physically present in a job that has historically required physical presence). From the perspective of learning and growth, though, it hasn't worked.

Many families saw this lack of creativity coming, so they rejected their school's plan for this year and aren't waiting to find out what the possible offerings will be for next year. They bolted, becoming a classic exit cohort á la Hirschman. I doubt many set out on their own driven mainly by the desire to leave behind the horrors of decadence, alas, but exit they did.

Early stories about the exit crowd from last summer mostly focused on wealthier families setting up "pandemic pods" and hiring tutors to manage instruction and provide childcare. Other families turned to homeschool to reduce the risk of contracting and spreading the virus. As the year has gone on, stories have emerged that focus on Black and Latino families and community-based organizations joining together to create and run alternatives to school like these in Boston. There is a consistent theme across many of the stories elevating the experience of Black families who have opted for creating a learning pod or chosen the school-delivered remote learning approach: very low trust in public institutions. (For a good summary of learning pods and their future prospects, read Lizzie Widdicombe's recent piece in The New Yorker)

While homeschools and learning pods represent a break from the sclerosis in the common school approach, there are significant barriers preventing these moves along the margins from becoming mainstream. As the pandemic recedes, there will be enormous pressure to return to school habits. In the work-from-home-while-schooling-at-home context of the pandemic, employers have generally been more understanding that so long as work gets done, caregivers need some flexibility during the day to coordinate learning. As the expectation shifts back to kids being in a school, does flexibility persist in a way that would enable some workers to keep and support their kids at home?

Nor are learning pods cheap. Some families can afford them and their decision to stick with a pod won't be as price sensitive. But in low-income communities where pods have taken root in community centers, legacy non-profits, and religious congregations, budgets were already tight. When these organizations have received grants to host learning pods, the funds are flowing from pandemic response allocations rather than the philanthropic allocations designated for education reform and improvement. Do philanthropies with an education mission step directly into the out-of-school learning space or are their loyalties (Hirschman again) more with the establishment approach, including public charters? The Koch- and Walton-backed Vela Fund is one such effort to invest education dollars to meet the pandemic moment outside of schools, but it's hardly sufficient.

We failed the "never let a serious crisis go to waste" test just as we failed Henry Smith and tens of thousands of his classmates. The opportunity to break free from many long-practiced orthodoxies in the American education system came and went while we debated 3 feet vs 6 feet classroom distancing standards.

Why the Chances for Renaissance are Small

Missing from the discussion above about our response during the pandemic are two important story lines that also point toward a persistently decadent future in American education. 1) The role of education politics both locally and nationally, and 2) the $195 billion in federal pandemic aid for K-12 (including some for private schools).

The politics of education

Schools operate under the governing authority of more than 1400 local education agencies (mostly school districts with local boards of education). State and local dollars account for the largest portion of education funding. It's a decentralized governing system that still produces more homogeneity than variation in school models and approaches. A school in Connecticut doesn't look altogether different than a school in Texas. Where there are differences, they are explained more by differences in family income and wealth than by specific, purposeful distinctions in curriculum and pedagogy. For instance, Staples High School (public) in affluent Westport, CT is more similar to Highland Park High School (also public) in Dallas, TX than it is to Bunnell High School in Stratford, CT not even 20 miles away.

There are two forces at play here: 1) the default orientation that college is the preferred option for high school graduates, and 2) how public dollars flow.

College: the North Star

College graduates benefit from an income premium compared to individuals with only high school degrees. It's not as large as it once was, though, even as more American adults now have a college degree. Regardless, the clarity of a the graph reinforces a narrative, "have college degree, make more money." For educators who care about long-term opportunities for their students, college completion has long been the ultimate goal. But not all degrees offer the same path to financial stability. And, when pursuit of the degree is funded with debt, it can make for a big hole to climb out of that has long term consequences (like a decline in home ownership).

Even as some educators see college as a pathway to opportunity, others use college admission rates to confirm their position among the best. College preparation scores makes up for more than half of the methodology used by U.S. News and World Report's ranking of 17,790 public high schools in the country (out of more than 24,000). It's easy to dismiss rankings like these. That they exist though speaks to how oriented the education system has become on a single measure and has used that measure to maintain a powerful connection between education, real estate, and tax revenue.

Most funding for schools comes from local sources, and states and municipalities have a limited number of options for generating revenue. Property taxes make up a significant portion of local education funding, creating a network of incentives.

-

More kids from the local high school who go to college boosts the perception that the high school is good.

-

That increases the desire to attend the school.

-

Since these are public schools, though, the tuition bill is paid via residential property purchases.

-

So, increased demand to attend "good schools" can sustain (and even increase) the value of local property.

-

Finally, completing the cycle, more valuable real estate creates a larger tax base from which to generate local revenue.

(Even in states, for example North Carolina, where the majority of education funding is allocated by the state, local counties often supplement state dollars in a manner similar to that of a traditional local property tax financing model.)

A public statement by a local superintendent or board of education that the purpose of the schools is something other than sending all students to college undercuts the accepted, correct position that a superintendent must have about purpose and immediately calls into question their belief in the potential of all children. Even more, a statement like this has the potential to threaten local property values while also raising good questions like "who decides which kids don't get college path academics?" Few superintendents can thread that needle, so "college for all" becomes the implied marching order against which countless policy and practice decisions are weighed.

We've exhausted the returns we can achieve by standardizing education even as we continue to carry a high standards banner year-after-year-after-year. It's not only that the system is stagnate and sclerotic, it's also lifeless in its exhausting repetition.

Follow the Money

With the "college for all" anchor set, school districts are then allocated millions (in some cases, billions) of dollars to run the schools. In reality, though, any one superintendent has very little influence over the district budget.

85-90% of school district budgets are non-discretionary. Salaries and employee benefits are the largest line item. 33 states require collective bargaining to establish compensation for teachers, and most of these states also allow collective bargaining for other school personnel – like principals, custodial staff, paraprofessionals, even school nurses. In 39 states, teacher strikes are illegal, so contract disputes are resolved through binding arbitration. Most resulting teacher contracts have a three-year term, and they spell out – in addition to salary schedules and available benefits – the majority of work expectations.

On top of this, the average tenure for a public school superintendent is 5-6 years (the data on superintendent tenure in the U.S. isn't as clear as one would think it would be). Superintendents are almost always hired by the school district's board of education, and 90% of boards of educations are composed of elected, volunteer members, mostly elected for four year terms. A victory for democracy? Not quite.

Far fewer voters turn out for school board elections because they mainly take place in off-cycle years. Groups that are likely to be directly impacted by the results of the election – notably employees of the school district – tend to make up a disproportional share of those who vote. The intrepid district leader with a vision for something new or different is dealt a tough hand: little budget flexibility, a boss broadly influenced by a key, politically active bloc of employees, and timelines governed by something other than disciplined implementation of an improvement strategy.

The infusion of federal cash in response to the pandemic will not change any of this.

In 2019, the federal government allocated $57 billion for primary and secondary education. Over the past 12 months in a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, an additional $195 billion has been set aside for schools. States and districts have a fair degree of latitude in deciding how to spend the money, so long as they spend it by 2024. Savvy local leaders see the downside of this windfall – it's one-time funding that won't be available for ongoing operating expenses over the long-term.

The money was appropriated to reopen schools, but the Congressional Budget Office projects only 5% of the most recent stimulus bill will be spent this year. Most districts do not have a clear plan for how they will spend the dollars, especially the latest allocation recently signed by President Biden. In the wake of the 2008 recession, the federal government allocated an additional $100 billion for primary and secondary schools as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. Primarily billed to save and even create jobs, that's not what happened in education. In a 2015 report, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis found that, "During the first two years following the act's passage, each $1 million of grants to a district increased education employment by 1.5 persons relative to a no-stimulus baseline. Moreover, all of this increase came in the form of nonteaching staff. The jobs effect was also not statistically different from zero." Granted, COVID stimulus funding directed to education hasn't been positioned to "save or create" jobs. Nonetheless, this wouldn't be the first time that money allocated for one purpose ended up being spent for something(s) else instead.

My hunch is that we'll see spending over the next two years go to physical plant improvements, summer school programs, teachers' bonuses, and ongoing expansion of internet connectivity and 1:1 device access. So far, I have not seen school or district plans to use the funding as a down payment on a substantive change to the student experience or to the core structure of the school day, yearly calendar, or academic plan.

Risk aversion, human capital constraints, off-cycle local elections, real estate driven financing – the system has become so massive as it's moved in one direction for so long that it's hard to image where a force large enough to change it would come from. If a global pandemic didn't do it, now what?

Imagining Renaissance in Education

Part three of The Decadent Society offers three possible "Deaths to Decadence," catastrophe, renaissance, and providential intervention. We just crossed off "pandemic" as a sizeable enough external catastrophe, so it's reasonable to assume there is not a catastrophe internal to the education system that would somehow disrupt the current reality. And while I pray "Thy kingdom come," any divine act would be so surprisingly miraculous that speculating is folly. That leaves renaissance.

Douthat's paths to renaissance include demographic change, technological developments, a postliberal politics, a revival of religion (in part driven by demographic change), or some combination of the above. I read them as a list of cultural levers (to the extent tech solutions are cultural before they become political).

This list maps pretty well onto the possible paths to renaissance in education. 1) more families choose exit; 2) tech; 3) affinity spaces as incubators of "postliberal politics")

What could exit look like?

-

Some share of families that left their assigned school in response to the pandemic don't go back post-vaccines and reopening.

-

Families spend a measurable amount of the expanded child tax credit signed into law by President Biden on educational resources and opportunities.

-

Families that relocated during the pandemic choose a different school option than what they'd selected before they moved.

-

Following on the expanded federal child tax credit, more state legislatures begin considering state-level child tax credits, educational tax credits or savings accounts, and vouchers.

-

The "school choice" coalition, increasingly led by people of color within the Democratic Party, gains traction as a powerful actor in Democratic Party agenda-setting.

-

A politically diverse set of philanthropies increase support for out-of-school learning initiatives that occur during school hours and are organized by non-school entities.

What does more technology in education look like?

Internet-enabled learning, long underutilized as a strategy for pedagogy and personalization took center-stage during the pandemic. It hasn't been perfect. But as a sector, tech's orientation toward iterative improvement cycles far surpasses anything comparable in the schools. The technology will keep getting better and better, and as it does it will require less and less professional administration. Here are a few areas to look for.

-

An increase in direct-to-consumer learning products that bypass business-to-school district sales channels.

-

Parents and students working together with software to create personalized learning profiles that are then delivered to schools as the desired path of study.

-

A gaming company buying and scaling a software product proven to teach children to read.

-

Activity-driven "camps" begin to operate during the traditional academic year. The focus is the activity, but time is allocated each day for participants to complete academic work or meet with an online academic tutor. Businesses are formed to help families match their child's learning/interest profile to various online and in real life providers.

-

More gap years between high school graduation and college enrollment as students participate in paid tech-driven fellowships, internships, and apprenticeships.

-

States creating (or accrediting) more online schools for kids ages 13-18.

-

Autonomous vehicles bringing down school transportation budgets even as kids access more of their community for learning.

-

More coworking spaces welcoming 13-18 year olds.

-

More proven, top tier performers, practitioners, operators in many different domains dedicating time and being compensated for teaching (outside traditional schools).

-

More publicly verifiable proofs of work between the ages of 16-24 with increased use of long-term, online pseudonyms. Rather than using a diploma as a credential, students have an online portfolio of work to show off.

What does "incubating postliberal politics" look like?

Douthat explores how "a dramatic political or ideological change [might come] first," preceding a tech-driven "up-from-decadence" process. One possibility exists "in which the oligarchic sclerosis of developed-world institutions is escaped by a refounding of virtuous communities on a more human and organic scale." Douthat goes on:

These communities would not fit a simple ideological pattern. They might encompass everything from new versions of the utopian communes of the 1960s and then nineteenth century, to libertarian experiments such as charter cities, to attempts to recreate the monastic communities that arose under Rome's imperial decay, to simple revivals of town-meeting democracy and other vanishing "Tocquevillian forms."

Which is to say that exit from the traditional system is both a pull and a push mechanism. As individuals and families might feel pushed out of the current system, they are also being pulled out by communal networks of shared viewpoint, belief, and vision – affinity. This will look similar to exit options described above but along a communal dimension (often relying on technology tools to launch and grow). A few early signs of movement and exploration:

-

Reconstruction.us is Kaya Henderson's, the former Chancellor of the D.C. Public Schools, new start-up. It's online and it promotes "unapologetically Black education." Many communities in the U.S. have had Saturday cultural classes for children to preserve rich religious and ethnic traditions. Some have even recreated the model of school not for the purposes of exit but from the necessity of being excluded in the first place.

-

The end of exam schools. Many of the students working to attend an exam school now won't now be admitted. These schools -- like Lowell in San Franciso, Thomas Jefferson in Fairfax County, Stuyvesant in NYC -- are often considered to be some of the best high schools in the nation. Will students instead enroll in the high school they are residentially zoned to attend, or in a private high school (that might be both more expensive and less academically rigorous), or...?

-

The creation of more post high school options that purposefully reject federal higher education funding of all kinds in order to encounter fewer regulatory mandates and develop a distinctly different educational plan and approach.

-

Charitable donations beginning to flow to non-tax deductible education efforts. Much of education, particularly higher education, is fueled by philanthropy -- tax-exempt institutions receiving tax-deductible financial contributions. Innovating along the path to new models for learning will be better served by matching greater risk with the possibility of large rewards. What emerges as the mechanism to enable both the growth of these businesses and the broader participation of students from underrepresented groups or parts of the U.S. without as much opportunity?

Douthat moves on to explore other postliberal pathways out of decadence. I prefer, however, the brief moment he allowed himself to hope: "small might be beautiful; exit and exile might eventually make the world anew."

Conclusion

Douthat doesn't pull any punches as he concludes his opening chapter. The melancholy starts early in The Decadent Society.

The truth of America and the West in the first decades of the twenty-first century, a truth that helped give us the Trump presidency but will still be an important truth when he is gone, is that we have not been hurtling anywhere -- except maybe in a circle. Instead, we are aging, comfortable and stuck, cut off from the past and no longer optimistic about the future, spurning both memory and ambition while we await some saving innovation or revelation, burrowing into cocoons from which no chrysalis is likely to emerge, growing old unhappily together in the glowing light of tiny screens.

That's a haunting paragraph. Marc Andreessen offered the most potent, as well as most practical, reply: "It's time to build."

Apart from the brief description of stagnation in education quoted (far) above, a deeper treatment of American education is one of the larger omissions in The Decadent Society. Andreessen, though, starts to fill the gap.

You see it in education. We have top-end universities, yes, but with the capacity to teach only a microscopic percentage of the 4 million new 18 year olds in the U.S. each year, or the 120 million new 18 year olds in the world each year. Why not educate every 18 year old? Isn’t that the most important thing we can possibly do? Why not build a far larger number of universities, or scale the ones we have way up? The last major innovation in K-12 education was Montessori, which traces back to the 1960s; we’ve been doing education research that’s never reached practical deployment for 50 years since; why not build a lot more great K-12 schools using everything we now know? We know one-to-one tutoring can reliably increase education outcomes by two standard deviations (the Bloom two-sigma effect); we have the internet; why haven’t we built systems to match every young learner with an older tutor to dramatically improve student success?

My hunch is that Douthat sees schools as inheritors of the decadence achieved by the generations that have long since graduated. A lagging indicator. A home safe for reactionaries rather than vanguards. And I wouldn't disagree with him. What's missed when we stop there, however, is the opportunity to decide something new, to make education – even from the smallest of starting points – fertile ground for the seeds of renaissance.

Until we make that choice, the "four horsemen" ride on.

Cover photo: "Seventh Grade." Anthony Camerano. AP. 1972.