The Old Default

Washington’s out. Local control is in. We go back to Eastern Tennessee to consider what this means.

Goodbye, Maryville.

In my previous post, we visited Maryville, Tennessee, to discuss the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), the current federal law governing K-12 education in the U.S. The law was drafted by former Senator Lamar Alexander, who summed it up by remarking, “Schools are still a national issue, but there is a consensus that the issue is not to be resolved from Washington." He added, “...the new law and the consensus that supported it make it clear that the federal role should be mostly limited to making us aware of how children are performing.”

So, Washington’s out. Who’s in?

The Senator, and more importantly ESSA, relies on the old default option, local control: “The responsibility for deciding what to do […] belongs to school boards, communities, and classroom teachers.”

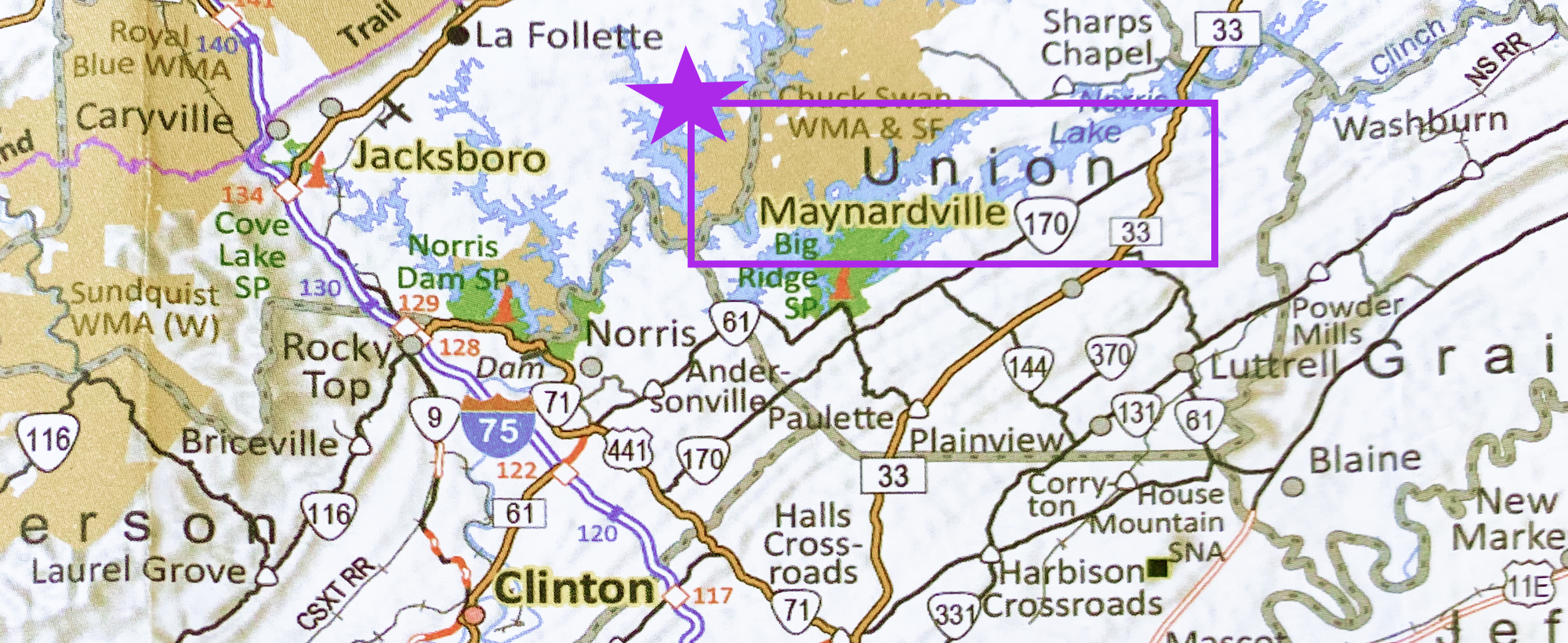

Union County, Tennessee, a hour-long drive heading north from the Senator’s hometown of Maryville, provides the setting for discussing the typical challenges inherent in the default option. These are challenges anyone concerned about the “national issue” of public education will need to confront and overcome.

Hello, Union County

20,000 people live in Union County, a rural county in northeast Tennessee. Around 4,300 students attend the public schools. To be fair, there are similar anecdotes from every state in the nation that would suitably illustrate the conflicts between state governments and local school boards and the difficulty of driving change in a local control model. Union County happens to be close to Maryville, so here we are.

Several years before the Covid closures, the State of Tennessee passed a law in 2011 allowing for the creation of virtual schools. Union County partnered with K12 Inc., a for-profit company, to open the Tennessee Virtual Academy. Enrollment swelled to 1500 including students who lived outside of Union County and were eager to register for a virtual school option. Legislative innovation, nice! Public-private partnerships, how ‘bout it! Linking rural communities to nation-wide networks, yes! More choice for families, incredible!

Tennessee also has a law directing the State Department of Education to issue grades to schools based on a variety of performance measures like student academic proficiency and attendance. When those grades are consistently low, the Department can intervene. Accountability, nice! Outcomes-based evaluation, yes! Prescribed actions in response to those outcomes, hot damn!

Results

Year 1: the Tennessee Virtual Academy earned the lowest possible score.

Year 2: the Tennessee Virtual Academy earned the lowest possible score.

Before Year 3, the state’s Commissioner of Education moved to close the school. A lawsuit was filed. The case was heard. The judge ruled against the state. The school remains open today. (Read more if interested: News report. Commissioner’s reflection. K12’s response to the Commissioner.)

In 2019, the most recent year in which schools were graded, the Tennessee Valley Academy again earned the lowest possible score.

Recap:

- The creation of the Tennessee law and of the school occurred in 2011. No Child Left Behind was the federal education law in 2011 which is also when the federal government was at its most active in education issues. (Also, this is about 5 years prior to the replacement of NCLB by ESSA.)

- Union County responded to the new Tennessee law by partnering with one of the largest online education companies in the U.S.

- The school opened and quickly became the school of choice for families and students residing in Union County as well as for those living in other school districts.

- The school’s performance in terms of student academic growth and attendance earned it the lowest possible score on the state’s school evaluation framework.

- The Commissioner took steps to intervene and was blocked by a lawsuit and subsequent court ruling.

- The school is still open today. Families are still choosing it for their child.

This particular episode was not a win under accountability-heavy NCLB. Neither is this a win for the local control of ESSA.

So, what

Across the late ‘90s through the early ‘00s, the expectation was that Washington’s involvement would provide the much-needed motivation and accountability for local efforts to improve education. Clear goals, clear measures of progress, and more active federal oversight would overcome the malaise keeping school performance stagnant in districts nationwide.

That’s not what happened. And, where there might have been a reserve of energy in local school systems, that energy was often directed in a reaction against Washington’s involvement rather than in local improvement efforts. Now, under ESSA, that accountability to the federal government has mostly been removed.

The default option means state and local governments – entities like the Union County Public Schools – have much more latitude to innovate and define their own measures of success. The default option is 14,000 local government agencies operating 100,000 schools. At a fundamental level, a commitment to public education today is a bet on the ability of the institution to drive improvement without centralized direction or accountability.

In a way, local control sounds like another way to say, “decentralization.” I have written about decentralization before, but I have mostly considered the ways in which decentralized options outside the current system would draw families away from public education. I continue to see that as a very likely possibility over time.

The more immediate development – as we’ve seen in Union County – is the return to decentralization inside the institution and its inability to govern and manage itself to achieve outcomes. The old default is, well, old. Making it new again remains the last, best hope for the public schools and the roles they play as a public institution in our country.